Introduction to Body Alignment Concepts

As we begin to understand more about the effects posture and mechanics have on overall health and injury prevention, body alignment is becoming a more discussed topic in fitness. Yoga, Pilates, and many other fitness programs speak of alignment frequently. There are several different approaches to alignment so let’s begin by defining what proper alignment looks like, later explore deviations, and ultimately expand on some things you, as the instructor, can do to help.

So what does ideal alignment/mechanics look like?

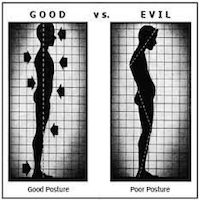

Most medical and movement professionals agree that the major joints should be aligned over one another while in a resting, standing posture. From the side (lateral) view, the ear, shoulder joint, hip joint, knee, and front of the ankle should be directly over one another. From the front or back (anterior or posterior) view, the shoulders, hips, and knees should be level and the feet should both point straight ahead or have a slight symmetrical turnout of up to ten degrees. The knees and feet should point in the same direction.

The alignment research I find most fascinating has been done by observing people and cultures in the way an anthropologist does. In Esther Gokhale’s book Eight Steps to a Pain-Free Back, she demonstrates posture differences with hundreds of photos of indigenous people and ancient sculptures from around the world. She compares the spines and body mechanics of people from modern western cultures, where back pain has been an epidemic for decades, to those who live in indigenous cultures, where back pain is rare. There are some astounding differences in the way our bodies look and move.

No matter what continent, the indigenous people and the sculptures consistently showed the deepest curve of the spine to be at the very base just above the sacrum (at L4/L5). The upper/thoracic spine and neck/cervical spine were long and mostly straight, with far less “S” curve than is considered normal in most modern anatomy textbooks. Many theories exist to explain why this may be and I will explore these theories in my next article.

Conscious vs Unconscious Posture, Movement, and Alignment

“Stand up straight” is something your mother may have said to you when you were a kid. This is an example of asking someone to consciously change their posture or alignment. We do it all the time as coaches, and we should. We ask people to be intentional in the way they move their bodies. “Point your knees the same direction as your toes. Relax your shoulders down away from your ears,” etc. These are common cues you might say in your indoor cycling classes. This coaching is essential, and something we should be doing as we teach students how to respect the design of their bodies, move well, and improve their abilities.

Sometimes, we have a student or several students who, no matter what we say and no matter how hard they try, cannot move their body into a position or in the way we are asking. The reasons for this and the way to address this issue vary greatly. People with out-of-balance alignment can be divided into two categories: those with structural alignment issues and those with neuromuscular alignment issues.

Structural Alignment Issues

When the actual bone shape affects the posture or alignment, this is a structural issue. A few examples include osteoporotic bone changes, genetic factors, or issues caused by an injury, such as a bone that was not set properly before it healed. When structural issues are present, exercises and cueing will be unlikely to produce changes for these folks. Furthermore, asking them to force themselves into a position may do more harm than good. This is one reason it is always best to encourage students to relax into better positions verses pull, tense, or force a joint. In an upcoming ICA article, I will give you a series of safe and effective cues to give riders when asking for conscious changes in position and mechanics.

Neuromuscular Alignment Issues

Where there are no structural issues but the alignment is imbalanced, this is typically caused by faulty neuromuscular patterns, compensations, or unconscious habits. This can look like an individual with one shoulder sitting higher and the individual has no awareness of the imbalance. Another common example is a torso that is rotated forward on one side, again with no awareness or effort of the individual. A rounded, slouching upper back (kyphotic) and head-forward posture are common issues that can lead to neck, back, shoulder, knee, or even hip pain. These standing alignment issues will show up on the bike as well and can lead to pain, decreased power output, and diminished performance. Often, conscious attempts to change these patterns is futile with little significant improvement until you disrupt the automatic pattern. Amazingly, breaking those patterns can be more simple than you might imagine.

Disrupting Faulty Neuromuscular Patterns

The images below are of a young crew athlete who came to me with knee pain. The most significant alignment issues I found after assessing her were her natural tendency to stand with her knees bent, with her pelvis tucked or posteriorly tilted, and her head in a forward posture. You can see her major joints were not aligned over one another. After doing a series of subtle exercises, we reassessed her resting alignment, with zero coaching from me about how she should stand, and these were the results. These pictures were taken on the same day. With regular practice of her exercise program, her knee pain went away and she went on to have a successful four-year career as a Division I college crew athlete. She now teaches indoor cycling!

As indoor cycling instructors we are not expected to do alignment therapy, but having a strong understanding of mechanics will allow you to help many people. There are several simple exercises you can to at the end of your classes in your cool-down that can help your riders with alignment issues. Stay tuned for lots more information on alignment and mechanics!